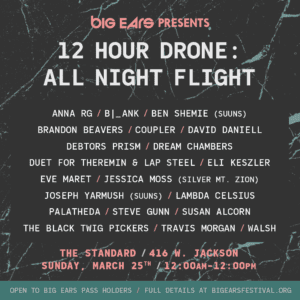

Behind the Scenes at Big Ears: Ben Smith, Curator of the 12-Hour Drone

In 2018, Big Ears hosted our first 12-hour drone, the “All-Night Flight.” From midnight on Friday until noon the next morning, a series of 20 artists performed sustained tones with no interruption. We asked curator Ben Smith to tell us about the process…

First up, what is drone?

Drone is just the sustaining and repeating of tones and sounds. Loops, resonance, and feedback contribute, too. You can hear drones across a variety of genres – metal, classical, psychedelic rock, electronic, pop. It predates genre. Predates a lot of confines like borders and time, too. Aboriginal Australians use the didgeridoo. Tibetan Buddhists use tonal chanting. Indian music features drones (from instruments like ektar, sitar, and tanpura) as the backbone of classical and folk music. It’s ancient but can connect experimental music to sacred ritual music to metal to electronic ambient. It’s kind of one of those “open to interpretation” styles of music. Drone can be harsh, discordant, chaotic. Or it can be ethereal, harmonious, ecstatic.

What draws you to this type of music? What does drone attempt to do for the listener?

It’s hard to describe what exactly draws me to it. My earliest exposure to it would be the more drone-y parts to Godspeed You! Black Emperor or the ambient bits of Sigur Rós – both of which I discovered early in high school (and I think led me on my musical journey). Those extended bits of songs that let me just zone out. Maybe I’m looking to just get lost in my thoughts? It’s super cool that – depending on the drone music – it can be uplifting and energetic and really blissful. Or it could just be heavy, full of dread. And anything and everything in between. Drone music attempts to do what all music and art does: make the listener feel. One way or another. It’s more hypnotic, though – so it’s easier to get the listener lulled into it. Listeners can hear so many different things in the drone, from an orchestra to waves to voices to more. And the actual vibrations from the sound hit your body and cause a rise in endorphins – so it’s making you feel – one way or another.

What inspired you to create the 12-hour drone at Big Ears last year?

The seeds for the 12-hour drone were planted when we presented Lou Reed’s Drones in 2015 at the Standard. For five hours on Friday and Saturday, Stewart Hurwood – Lou Reed’s guitar tech – would use a handful of Reed’s guitars and amps to create this feedback wall. It was really dreamy. I talked with Hurwood after one of the performances and he converted me to the drone. The seed sprouted when I attended the 24 Hour Drone in Hudson, NY – put on by Basilica Hudson and Le Guess Who. It was an amazing experience. It was an event that existed outside of time – with the seamless sets. Performers traded off sets, transforming the drone of their predecessor and passing it on to their successor. It’s unlike any concert I’ve ever been to. While there were “set times”, it was fluid and you weren’t there to see a “set”, but to hear and be inside this envelope of sound which was a really transformative experience. I was fading in and out of consciousness between 3 and 5 am and it was hard to tell what was real or what was dream. At the end of the 24 hours, I knew this needed to happen at Big Ears. With the special counseling and guidance of Melissa auf der Maur, Bob van Heur, and Jessica Moss, I was able to put together a really excellent line-up of both musical and visual artists.

What was it like to be in the room? Any specific memories or moments that stand out?

The room felt like some sort of alternate reality. Once you stepped into the room, you weren’t greeted with a standing audience, but one sitting or lying down on the floor. Mapped projections by Marcus Sisk and his team decorated the back and sides of the room. The stage had visuals by John Kelley, Emily Bivens, Christopher Spurgin, and Marcus Sisk. Since it was twelve hours of continuous, non-stop drone, the air in the room was never still. It felt like we were all removed from the real world in some weird sense. Everyone was there to get a sonic bath, away from time. A few moments stand out: Eve Maret’s set, where she attached a contact mic to a pair of clippers and shaved her head. It really brought home the transformative nature of the drone – and in an immediate, physical way. David Daniell’s performance was otherworldly and coupled so well with the visuals projected behind him. (None of the visuals were planned according to the artists!) And then there was the fire alarm at 6AM – the half way point. It was so weird. At first, most attendees and performers thought it was part of the drone. It interrupted the drone for 27 minutes, but we resumed with Brandon Beavers performance – as no attendee left. They all came back in and got back to droning out. Talking with one person, they said it felt like a dream, like it wasn’t really happening. And that it became part of the experience. So coming soon – 12 Hour Drone 2: More Fire Alarms! (Not really — I don’t want that to happen again) But at the end of it – noon the next day – I felt a certain lucidity (I think most people called it delirium) and Eli Keszler’s percussive drone set was the perfect ending. It was wild walking out of the venue into a sunny day – back to the real world, I guess.

What advice would you give to someone on their first “all-night flight”?

Bring pillows and a sleeping mat… many people drift in and out of sleep during the drone. If you commit to the full thing, you’re there for 12 hours so pack accordingly. Water bottles, snacks, coffee, whatever you’ll need. At the 24-Hour Drone in Hudson, I saw people drawing in sketchbooks, reading, playing Magic. Prepare to have fun!

How will you approach curating future drones?

I have a lot of ideas for the next drone. From the curatorial standpoint, I don’t think I’ll do much differently. It’s important to bring in local and regional artists, as well as already featured Big Ears performers. We had a big Nashville group this last year, so maybe I’ll look toward Atlanta, Asheville, and Louisville. I’d love to have more sacred music in the line-up. More international representation, too. Lots of big ideas…

Big Ears 2018 Drone Lineup: